Toronto

Marianne K. Miller (Independent Scholar) and Dr. Hilary Justice (JFK Library).

Updated 11/2023.

Ernest Hemingway lived in Toronto, Canada, twice, for a few months in the winter of 1920 and a few more in 1923-1924. His ongoing relationship with The Toronto Star newspapers provided friendships, opportunity, and financial support when he needed it. His and his wife Hadley's only child, John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway (nicknamed Bumby; later: Jack), was born there on October 10, 1923.

Explore this page:

Timeline: Toronto: 1920, Interlude: Paris, Toronto: 1923-24

Relationships

Works: Inspired by Toronto, Written in Toronto

Related Pages

Toronto Timeline

1920

January

Ernest Hemingway had spent the summer and fall of 1919 in Northern Michigan reading, writing, fishing and camping with friends. Despite believing he had written some great stories during his stay, he'd had no luck selling them. He also spoke to local audiences about his war experiences. Harriet Connable, a Petoskey, Michigan, native, heard Hemingway speak. She invited him to Toronto to be a paid companion for her son, Ralph Connable, Jr. Hemingway arrived in Toronto in mid-January, 1920.

Harriet's husband Ralph Connable, Sr., the head of Woolworth department store in Canada, was to pay Hemingway $50.00 a month plus expenses while the rest of the family vacationed in Florida. Fifty dollars a month plus lots of time for his literary pursuits suited Hemingway well. He settled into the Connable mansion, and Ralph, Sr., soon introduced him to the Toronto Star newspaper.

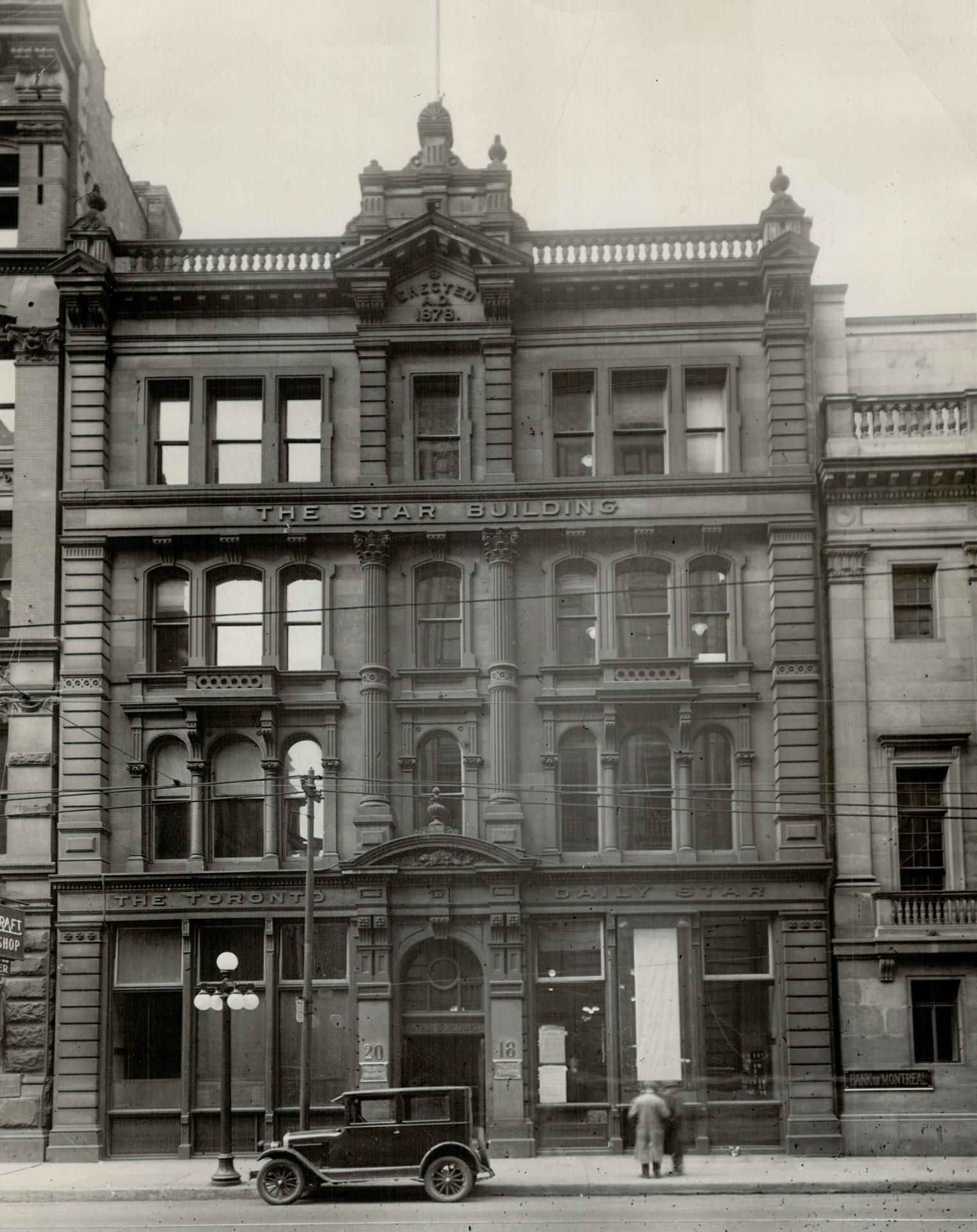

Hemingway haunted the Star offices so often that J. R. Cranston, editor of the Star Weekly, offered to pay him half a cent to a penny a word for any features they published.

February

Hemingway’s first piece, about renting art, was published on February 14, 1920. For his second piece, about the danger of accepting a free shave, he not only got paid, he got his first-ever byline.

March-April

In March, Hemingway had three pieces in the Star Weekly. In April, many more, including three pieces in the April 10 edition alone: one on trout fishing, another on dentistry and a third concerning two old soldiers talking about the war. Multiple pieces in one edition was a practice that he would repeat often throughout his relationship with the Star Weekly.

His writing attracted the attention of John Bone of the daily paper. Hemingway’s first Toronto Daily Star piece, about a post-war buying commission with which Ralph Connable was involved, appeared with no byline at the end of April. That same month, Hemingway wrote his mother that he was no longer accepting money from Mr. Connable but living off the money he made from the paper.

Hemingway had an enjoyable life in Toronto. In addition to the Connables, he made a number of good friends at the paper, Greg Clark, Jimmy Frise, Jimmy Cowan. Hemingway’s best friend from Petoskey, Dutch Pailthorp, was also living in Toronto. Hemingway reports going to the opera, playing tennis, playing bridge, horseback riding, going dancing and entertaining friends at the Connable mansion. He also made a trip to Buffalo to visit Arthur Thomason who had served with Hemingway in Italy.

But as early as March of 1920, he was planning to return to Michigan in late spring to fish and camp with his pals.

May

Hemingway left Toronto.

June

In his June 1920 thank you letter to Harriet Connable, Hemingway tells her he misses Toronto and the Connable family, calling them the nicest people he has ever known.

Despite the fact he’d left Toronto in May of 1920, his pieces still appeared in the Star Weekly. The summer ones reflect what he was up to. They were about camping, mosquito repellant, and trout fishing.

The Star may have paid little, but it continued to recognize his writing ability and, perhaps, increase his confidence. Although he moved on to Michigan, Chicago, and then Paris, Hemingway maintained his connection to the Star.

Interlude: Paris, 1921-1923

The Ernest Hemingway who returned to Toronto in 1923 was a very different man.

His personal life had changed dramatically: he was married to his first wife, Hadley Richardson Hemingway (1891-1979), and an expectant father.

Professionally, he was no longer an aspiring writer whose fiction was being rejected. His talent had been recognized by authors Sherwood Anderson (1876-1941), Ezra Pound (1885-1972), and Gertrude Stein (1874-1946), and bookstore owner and publisher Sylvia Beach (1887-1962). With Pound’s help, he had been published in literary magazines. He had published his first book in Paris in August, 1923, Three Stories and Ten Poems, and would finalize the cover art for his next book, in our time, from Toronto. (in our time—all lower-case letters—is sometimes called "the Paris in our time" to distinguish it from the 1925 New York publication, the In Our Time readers buy today.)

Things were starting to happen for him in Paris, but Hadley was pregnant, and they wanted their baby born in North America. Having no desire to live near Hemingway's parents (from whom they concealed the pregnancy for months), they chose Toronto, where Hemingway had an established connection to the Toronto Star. His connection made it easy to secure a full-time position, and they moved, planning to provide their baby a stable first year.

1923

August-September

On August 26, 1923, when Hadley was eight months pregnant, they left Paris for Canada. They had not yet told his parents they were expecting a child.

Hemingway returned to Toronto with a heavy heart. Despite having enjoyed Toronto in 1920, and despite the Toronto Star's enthusiastic support of his journalism and fiction, Hemingway saw his return as a serious and risky detour in his literary career.

Although fellow Star reporter Greg Clark (1892-1977) told him that when he came back he would be in a position to “tear into things and write your name in the stars,” Hemingway must have known that being a full-time staff reporter would take away time for literary work. Gertrude Stein, one of his Paris mentors, had warned him that ‘[Journalism] would use up the juice needed for [writing].”

Return to The Star

There was a great difference between Hemingway's life as a freelancer and sometime foreign correspondent and the daily grind of a staff reporter.

His first day on the job, Hemingway interviewed Sir Donald Mann, the head of the defunct Great Northern Railway, who had just returned from a trip to Russia. That night, he was sent to cover the prison break at Kingston Pen. In his first month, he reported on a possible stock fraud from Sudbury, interviewed Lord Birkenhead, and covered Lloyd George, Britain’s former Prime Minister, on the beginning of his North American tour. Later he interviewed Sir William Lister and Dr. Federick Banting, the Nobel Prize winning discoverer of insulin. These were not unimportant stories, but the pace was exhausting.

City editor Harry Hindmarsh's (1857-1956) treatment of him rankled. Apparently believing that this young Paris upstart needed some humility, Hindmarsh frequently assigned him multiple stories and, Hadley's imminent due date notwithstanding, sent him out of town. Hemingway, never shy about touting his own accomplishments, felt Hindmarsh's treatment lacked the respect and consideration he'd earned while in Europe.

Working with his old friends was inadequate comfort, but meeting Morley Callaghan (1903-1990), a student and talented fledgling writer who became a long-term friend, helped a little. Hemingway also took some time to attend boxing matches in Toronto or while away on assignment.

Most importantly to the Hemingways, Toronto was not Paris. It wasn't even New York. In Hemingway in Toronto: A Post-Modern Tribute, David Donnell describes the Toronto of 1923 as “large and prosperous," but "[a] more frontier and puritanical city than New York.”

Hemingway had no time to write; he worried he was stagnating.

Domestic Life

While Hemingway was on assignment in Kingston to cover the prison story, Hadley Hemingway rented an apartment in a fairly upscale building at 1599 Bathurst Street, not far from the Connables' home. It cost much more than their apartment in Paris.

Although early biographers insist that the Hemingway's Toronto apartment was much like their 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine apartment in Paris—small, cramped, and out-of-date—the advertisement Hadley responded to declares otherwise:

The Bathurst Street apartment was spacious, sunny, and designed for fresh air circulation, all highly desirable to ensure a healthy first year for their first child. One can only imagine Hadley's relief at the up-to-date kitchen and laundry facilities, as well, especially considering that their Paris apartment had been the opposite of this: small, dark, cramped, not designed for air-flow, and offering only one shared, in-floor latrine per story.

A few days later, Hadley wrote to Ernest’s parents and told them about the baby’s imminent arrival.

As the fall wore on, the Hemingways grew concerned about the investments in Hadley’s trust fund, the income from which was crucial to their plans to return to Paris. Requesting answers from Hadley's financial advisor and family friend, George Breaker, went nowhere. Hemingway grew more suspicious. But Hadley's ties to Breaker were important; she kept searching for an explanation.

Marital friction ensued, no doubt exacerbated by the contrast between their Paris lifestyle (a tiny, cheap apartment in a working-class neighborhood) and their Toronto one (a large, more expensive apartment in an exclusive neighborhood), and the individual and mutual pressures the Hemingways were facing.

Meanwhile, Hemingway was corresponding with Paris friend and publisher William "Bill" Bird (1888-1963), whose Three Mountains Press was readying in our time for publication, working on ideas for the cover layout.

Bird's correspondence and their work on in our time's intricate, newspaper-inspired cover might have been a bit of an oasis for Hemingway, but Bird was also looking after the Hemingways' dog, and his letters brought further emotional burden: their dog was sick and soon died.

October

Despite Hemingway's protestations to Harry Hindmarsh, and with his first child on the way, Hemingway was sent to New York to cover the visit of former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945). Lloyd George had led the British government through World War I, but was out of power, with his political influence at a low ebb. Hemingway chafed.

October 10: While Hemingway was in New York, Hadley went into labour. Hemingway missed the birth of his first child, John Hadley Nicanor (Bumby; Jack) Hemingway.

On his return, Hemingway exploded at Hindmarsh, telling him he would never forgive him and, further, that all work would now be done with “contempt and hatred for him and his bunch of masturbating mouthed associates.”

“Consequently, position at office highly insecure.”

– Ernest Hemingway in a letter to Ezra Pound

He wrote to Bumby's godparents, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967), that "I have understood for the first time how men can commit suicide simply because of too many things in business piling up ahead of them that they can’t get through.”

Turning Point

The baby’s safe arrival and the trip to New York proved a turning point for Hemingway's relationship with Toronto.

While in New York, Hemingway obtained a copy of The Little Review – Exiles Edition which contained one of his poems and several short fiction pieces titled In Our Time, reminding him of his true calling.

Shortly after October 10, there is more good news. Edward J. O’Brien (1890-1941), whom Hemingway had met in Rapallo in the spring, wrote asking to publish Hemingway’s "My Old Man" in The Best Short Stories of 1923. O’Brien wanted to dedicate the volume to him and asked whether Hemingway had enough stories for a complete book. (O’Brien misspelled Hemingway's name in his letter and in the dedication, calling him "Hemenway.")

Exhausted, over-worked and worried as he was, Hemingway had not lost his sense of humor. He wrote to Sylvia Beach, self deprecatingly calling the anthology "The Best and Worst Short Stories of 1923."

More Problems at The Star

Hemingway had entrusted some documents for a story-in-progress to Hindmarsh; Hindmarsh lost them, and Hemingway exploded again.

Hemingway, overwhelmed, couldn't eat and developed insomnia. Hadley, meanwhile, was having trouble nursing their baby; it was almost unbearably painful.

The young family was struggling, and Hemingway couldn't write. His stories were dying in his head.

“For Gawd sake,” he begged Ezra Pound, “keep on writing to me. Yr. letters are life preservers.”

The Hemingways decided to abandon Toronto and to return to Paris early.

The Star Weekly

Hemingway arranged with J.R. Cranston, the Star Weekly editor for whom he'd started working in 1920, to write a series of articles in exchange for enough money to purchase tickets back to Paris. When Cranston agreed, Hemingway resigned from his staff position under Hindmarsh and went to work for Cranston. (The official date of his official resignation is unknown; it's possible he hedged his bets, writing for both The Star and The Star Weekly through the end of October.)

October 20: The Star Weekly publishes Hemingway's "Bullfighting--A Tragedy."

October 27: The Star Weekly publishes "Pamplona in July."

At least subconsciously, Hemingway was on the path toward his first major novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926).

November

Hemingway wrote so many pieces for The Star Weekly this month that the Weekly assigned him aliases, including "John Hadley" and "Peter Jackson."

This month he was once again able to write fiction. He had made a mental shift, realizing that security isn’t everything, particularly if it keeps you from your mission.

November 4: Hemingway writes his parents that he, Hadley, and John might go back to Paris in January.

On the back of an unsent letter also dated November 4 (to Larry Gaines, a Canadian boxer), Hemingway wrote page 9 of the earliest surviving manuscript of "Indian Camp."

November 6: Hemingway writes to Sylvia Beach, saying, “We will probably see you in January.”

November 11: Hemingway sends literary critic Edmund Wilson a copy of Three Stories and Ten Poems, asking demurely where he might, as an unknown name, get it reviewed.

November 17: Three Hemingway pieces appear in the Star Weekly: one on trout fishing in Europe, one on water levels on the Great Lakes, and one on the Notre Dame gargoyles in Paris.

November 18: Hemingway writes to Edward O'Brien to ask how many stories one needs for a book.

November 24: Seven pieces by Hemingway appear in this week's Star Weekly edition.

December

This month, Hemingway continues his impressive output for the Star Weekly, publishing 14 pieces, and writing three more that will appear after his January departure.

The date of Hemingway's official resignation from local work for the Star is unknown. His letters and Cranston’s autobiography strongly suggest it was in November. He nonetheless kept open the option for more foreign correspondent work should he need it (which he didn't).

With the help of their friends, Ernest and Hadley Hemingway, knowing they will break their lease, start to quietly move their possessions out of 1599 Bathurst Street.

Just before Christmas, Hemingway made a quick trip to Oak Park, Illinois, to say goodbye to his family. His elder sister, Marcelline Hemingway Sanford, recounts this visit in her memoir, At the Hemingways.

1924

January

January 12: Friend Jimmy Cowan's wedding was held in the Hemingways' bare apartment. That night, the Connables threw a farewell party for the Hemingways.

January 13: That morning, the Hemingways left Toronto on their way to New York to sail back to France.

Their one-year stay lasted only four months. (Follow Ernest and Hadley back to Paris.)

Toronto Relationships

In Toronto

The Connable family: Harriet Connable, who first invited Ernest Hemingway to Toronto; her husband Ralph, Sr.; and their son, Ralph, Jr. Ralph and Harriet Connable were fun-loving and supportive; parental figures more light-hearted than Hemingway's own. Like Ernest, Ralph Sr., hated "phonies"; he would dress up like a tramp and callout his rich friends when they shooed him away from their door or their church. Sometimes, he dressed up like a woman.

The Connables shared Ernest's love of Michigan. Ralph, Sr., shared many tales of tramping through the woods at night or bringing medicine to a sick native child from the years he worked in his father’s business. He was a well-loved man about town and a philanthropist; his company, Woolworth's, was a big advertiser in the Star, and he moved in the same social circles as the Star’s president, Joseph Atkinson. It is possible that he used his influence to help Ernest's transfer back to the Weekly after the blow-ups with Hindmarsh.

Hadley was visiting the Connables when she went into labor; they drove her to the hospital.

At The Star

Morley Callaghan, staff writer at the Star; later, renowned author. Callaghan would move to Paris in 1929, joining friends Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald and their expatriate literary circles. He later wrote a memoir of those last moments of the vibrant 1920s expatriate community, That Summer in Paris (1963). He recalled his first hint about Hemingway: one day at the end of the summer of 1923, Jimmy Cowan whispered to him that “A good newspaperman is coming from Europe to join the staff.” A month or so later, he met Hemingway. Hemingway thought Callaghan showed talent and would often meet with him to discuss writing. Like Hemingway, he was never keen on newspaper work. Harry Hindmarsh fired him (five times), but Callaghan insisted they parted amicably, saying he never hated the city editor the way Hemingway did. Of Hemingway's mood during his second Toronto stay, Callaghan notes, “I could see it wasn’t only the job that was bothering [Hemingway].” Callaghan found the silver lining, though, continuing, "If it hadn’t been for Hindmarsh, Hemingway might have remained a year in Toronto, he might not have written The Sun Also Rises, and I might have settled into newspaper work."

Greg Clark: Clark started as a cub reporter at the daily Star before WWI. He was a decorated WWI hero who fought at Vimy Ridge. After the war, he returned to the Star as a staff writer on the Star Weekly, where he met Hemingway in 1920. Like Hemingway, he also submitted pieces to the Star Weekly, although he wasn’t paid extra for doing so; Clark introduced Hemingway to Weekly editor J.R. Cranston.

In Cranston's memoir, Ink on My Fingers, he remembers Clark as overflowing with ideas and having the ability to find (or create) the fun in any situation. And, like Hemingway, Clark loved fishing.

Hemingway kept in touch with Clark during his early Paris years.

It's possible that Hemingway named his youngest child, Gregory, after Clark.

Clark quit the Star in 1946 in protest over Hindmarsh's treatment of his staff.

Jimmy Cowan: Feature writer at the Star. In 1921, at the age of 20, James Cowan founded a literary magazine called The Goblin and became its Editor in Chief. He was lucky enough to be presented with a copy of Three Stories and Ten Poems when Hemingway returned to the Star in 1923. It is inscribed, “This book is the property of James Cowan – he is not responsible for it – nor did he buy it. It was presented to him by the author.” His wedding took place in the Hemingways' apartment in January 1924, just before they left to return to Paris; Hemingway stood with him as his best man.

J.R. Cranston, editor of The Star Weekly. The Weekly's small budget meant their pages were open to newcomers, including Ernest Hemingway. In his memoir, Ink on my Fingers, Cranston remembers, “Greg Clark brought a stranger to my door.” … “Boss,” said Greg, “this fellow says he can write, and he wants to do something for us.” So began Hemingway’s relationship with the Star.

Jimmy Frise: In 1910, at the age of 19, Jimmy Frise found work as an illustrator at the Star. He was injured at Vimy Ridge continued to draw after he returned from WWI. Starting in 1920, he shared an office with Greg Clark. He, too, loved fishing and hunting. He also loved to chat with visitors to the office and this would have included young Mr. Hemingway. Frise often illustrated the humourous pieces Clark wrote in the Weekly. It was the beginning of a life-long association. When Clark quit the Star in 1946, so did Frise.

Harry Comfort Hindmarsh, city editor for The Toronto Star. In Hemingway - The Toronto Years, William Burrill describes Hindmarsh as “a brusque beefy man of six foot two with a short military haircut and a stiff military bearing. He did not expect his reporters and editors to like him - in fact, he knew most of them were scared stiff of him – but he did expect them to obey him without question.”

Hindmarsh, whose father-in-law owned the paper, would send a whole gang of reporters to any breaking news scene so that the Star reporters were not just in competition with reporters from other papers, but with each other. According to Burrill, Hindmarsh broke in new reporters by “putting them in harness," working them hard, day and night. It was his practice to reward outstanding work with punitively dull assignments to keep egos in check and control his staff.

J.R. Cranston described Hindmarsh as “[ruling] by fear,” a “sadist [who] took delight in breaking or humbling men’s spirits." In his memoir, Cranston concludes that, “[M]en of ability and strong individuality found his rule tyrannical … and were often provoked to rebellion that ended in resignation or dismissal.”

Correspondents

Hemingway's correspondence with his Paris friends proved a lifeline during the dark months of 1923-24, particularly Sylvia Beach, Bill Bird, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas.

Professional correspondence with Edward J. O'Brien, publisher of annual Best Short Stories books, provided affirmation and encouragement of his fledgling literary career at a crucial time.

Less welcome was correspondence with George Breaker, the husband of Hadley Hemingway's best friend, Helen. He had walked Hadley down the aisle at her wedding, and he managed (Hemingway would say mismanaged) her trust fund.

Works Inspired by Toronto

Although "Cat in the Rain" is set in Rapallo, Italy, the story's emotional content and plot resonate powerfully with the Hemingways' time in Toronto. In the story, a lonely wife is largely ignored by her husband, and she receives a cat as a gift from a caring hotel manager (padrone, "host," Italian; shares a root with padre, "father"). When Ernest Hemingway returned from one of his out-of-town assignments for the Toronto Daily Star, he, an expectant father, brought his lonely wife, Hadley, a cat. Hemingway wrote this story in March and April of 1924, not long after the Hemingways returned to Paris.

Although Hemingway may not have realized this consciously, in his journalism, he was already rehearsing material that would inform The Sun Also Rises (1926) and Death in the Afternoon (1932), a book he described as having "long-wanted to write."

Works Written in Toronto

Since the Star gave journalists a free writing hand and their editors were instructed to preserve their writers' individual styles, Hemingway's Toronto journalism allowed him to refine his voice and focus (for features, if not assignments) on concerns that appear throughout his writing life: fishing, hunting, food, the environment, Spanish bullfighting, veterans, smuggling, European culture, &c.

In addition to his journalism, Hemingway wrote the earliest draft of "Indian Camp" while in Toronto.